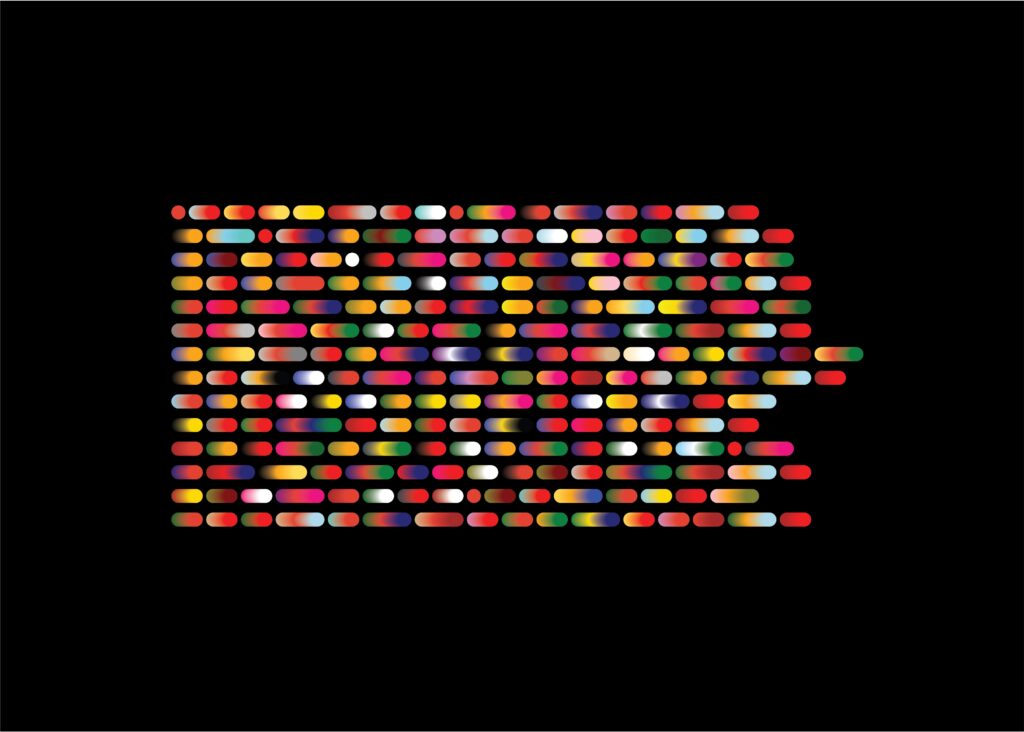

The project was completed in 2008 as “Chromatophonography,” or, in other words, translating vocal signs of Persian classical poetry into colorful signifiers. The coding is done not according to prosody or the letters used but rather by phonetics or pronunciations of the words. Here, only the formal aspect (colorful codes) is sustained, and the poem is emptied of meaning, visually rendering the poem’s music.

Relationship between colors

In physics, the relationship between colors and sound waves is called ‘synesthesia’ /ˌsinəsˈTHēZHə/, which is a neurological phenomenon where stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in another path. For some people with synesthesia, certain sounds are associated with specific colors. However, this is not a universal experience and is not directly related to the physics of sound waves. The perception of color is a result of how our eyes interpret different wavelengths of light, while the perception of sound is a result of how our ears interpret different frequencies of sound waves. While there may be some overlap in how the brain processes these sensory inputs, there is no direct relationship between the colors associated with sound and the physics of sound waves themselves. The logical selection of colors for the NATO phonetic alphabet is based on several factors. First, the colors are chosen to be easily distinguishable from each other, even in low-light or high-stress situations. For example, red and blue are highly contrasting colors that are easily differentiated. Second, some of the color associations are based on the initial letter of the word. For example, “Alpha” starts with the letter A, commonly associated with red. Similarly, “Bravo” starts with the letter B, often associated with blue. Third, some of the color associations are based on common cultural associations. For example, “Golf” is associated with the color purple because golf tournaments often use purple as a prominent color. Overall, the selection of colors for the NATO phonetic alphabet is designed to be practical and easily understandable in various contexts.

The four characteristics of sound are

vowel | color | HEX code | Persian sign | syllable |

ā | Red | FF0000 | آ، ا | V |

b | Blue | 0000FF | ب | C |

c | Yellow | FFFF00 | چ | C |

d | Green | 008000 | د | C |

e | Orange | FFA500 | ِ | V |

f | Pink | FFC0CB | ف | C |

g | Purple | 800080 | گ | C |

h | Brown | A52A2A | ح، ه | C |

i | White | FFFFFF | ای | V |

j | Gray | 808080 | ج | C |

k | Black | 000000 | ک | C |

l | Light blue | ADD8E6 | ل | C |

m | Dark green | 006400 | م | C |

n | Navy blue | 000080 | ن | C |

o | Gold | FFD700 | ّ | V |

p | Peach | FFE5B4 | پ | C |

q | Turquoise | 40E0D0 | ق، غ | C |

r | Rose | FF007F | ر | C |

s | Silver | C0C0C0 | س | C |

t | Tan | D2B48C | ت | C |

u | Maroon | 800000 | او | V |

v | Violet | EE82EE | و | C |

x | Charcoal gray | 36454F | خ | C |

y | Mustard yellow | FFDB58 | ی | C |

z | Olive green | 808000 | ز | C |

a | vermilion | E34234 | َ | V |

š | sky blue | 87CEEB | ش | C |

ž | rusty orange | 8C3C10 | ژ | C |

The codes follow these rules:

Since different consonants of the Arabic alphabet from which Persian script is derived are pronounced in the same way, poems with Arabic lines are avoided

Each line of poetry is coded in one line

About Persian meters

Persian meters are the patterns of long and short syllables, 10 to 16 syllables long, used in Persian poetry.

Over the past 1000 years, the Persian language has enjoyed a rich literature, especially of poetry. Until the advent of free verse in the 20th century, this poetry was always quantitative—that is, the lines were composed in various patterns of long and short syllables. The different patterns are known as meters (US: meters). Knowledge of meter is essential for someone to correctly recite Persian poetry—and also often since short vowels are not written in Persian script, to convey the correct meaning in cases of ambiguity. It is also helpful for those who memorize the verse.

Meters in Persian have traditionally been analyzed in terms of Arabic meters, from which they were supposed to have been adapted. However, in recent years it has been recognized that for the most part Persian meters developed independently from those in Arabic, and there has been a movement to analyze them on their own terms.

An unusual feature of Persian poetry not found in Arabic, Latin, or Ancient Greek verse is that instead of two lengths of syllables (short and long), there are three lengths (short, long, and overlong). Overlong syllables can be used instead of a long syllable plus a short one.

Persian meters were used not only in classical Persian poetry but were also imitated in Turkish poetry of the Ottoman period and in Urdu poetry under the Mughal emperors. That the poets of Turkey and India copied Persian meters, not Arabic ones, is clear from the fact that just as with Persian verse, the most commonly used meters of Arabic poetry (the ṭawīl, kāmil, wāfir, and basīṭ) are avoided, while those meters used most frequently in Persian lyric poetry are exactly those most frequent in Turkish and Urdu.

source: wikiwand

Quantitative verse

Classical Persian poetry is based not on stress but on quantity, that is, on the length of syllables. A syllable ending in a short vowel is short (u), but one ending in a long vowel or a consonant is long (–). Thus a word like ja-hān “world” is considered to have a short syllable plus a long one (u –), whereas far-dā “tomorrow” consists of two long syllables (– –). A word like na-fas “breath” is usually considered to have a short syllable plus a long one (u –), but if a vowel follows, as in na-fa-sī “a breath”, the second syllable is short (u u –).

A characteristic feature of classical Persian verse is that in addition to long and short syllables, it also has “overlong” syllables. These are syllables consisting of any vowel + two consonants, such as panj “five” or dūst “friend”, or a long vowel + one consonant (other than n), for example, rūz “day” or bād “wind”. In the meter of a poem, an overlong syllable can take the place of any sequence of “long + short”. They can also be used at the end of a line, in which case the difference between long and overlong is neutralized.

In modern colloquial pronunciation, the difference in length between long and short vowels is mostly not observed (see Persian phonology), but when reciting poetry the long vowels are pronounced longer than the short ones. When a recording of Persian verse is analyzed, it can be seen that long syllables are on average pronounced longer than short ones, and overlong syllables are longer still (see below for details).